I was my father's favorite.

"What's that Louisa?"

Let me rephrase that.

My Dad liked me best.

"Hey, this is my story."

The first words that I can remember my dad sing, went like this.

"Down by the station, early in the mornin'."

I was sitting cross legged in the bathtub and was up to my chin in bubbles, with my two younger sisters, Louisa and Kiki, on either side.

"See the little puffer-bellies all in row."

I'm not sure how old we were, but, it has been five decades since we all three fit in a tub together.

"See the station master pull the little lever."

Boy could my dad sing.

"Puff, puff."

Hang on. Here comes our part.

This is when Kiki, Louisa and I made our pruned little hands into fists and we pulled on an imaginary rope, to blow the horn.

"TOOT!!! TOOT!!!!" we yelled.

And now, back to my dad.

"Away we go!"

"Sing it again. Sing it again," we would beg.

And so he would sing it again.

And then one more time.

"That's it girls. I told you that was the last one," he would say. "Come on out of there if you want some popcorn."

So we climbed up and over the slippery wall and stepped onto the rug, to have a towel thrown over our heads and were spun around and sprinkled with talcum powder.

I was the lucky one.

I inherited my dad's musical talent.

In fourth grade I signed up to be in the Crestwood Elementary School Orchestra. Because I could.

As we were lining up to leave the classroom, Mrs. Lawrenz says, "Millie, stop in and see me after school."

I could not imagine why my music teacher would want me to visit her after the 3:15 bell.

"So," she says when I arrived. "You want to play the violin?"

"Yes," I answered.

"And you like the violin?" she asked with her hands on her hips.

"Yes," I lied.

"Well, Millie, I think we should do a little test."

"A test?"

"Nothing big. I am just going to play a note on the piano and then I would like you to sing it."

"What the?" I said, trying to keep my eyeballs in their sockets.

She sits down at the piano, places her index finger on a white key and holds it down for a couple of seconds.

"Okay, now hum that note."

"Hmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmm."

"How about this one?"

"Hmmmmmmmmmmmmm."

Her middle-aged finger holds down yet another key.

"Hmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmmm."

"Try this one," she says.

I did.

And then again and then again we repeated this horrific game.

Finally it ended.

Mrs. Lawrenz pushes the piano bench back. She stands up and smoothes down her wrinkled skirt that landed just above her tired, panty-hosed knees and says, "Millie, I really appreciate the fact that you really appreciate music. And I know that you love to sing. So what I am thinking is that maybe you should stick with our choir."

"But, why?"

"Well, Sweetie," she says, struggling to find the right words. "You are what they call, tone deaf."

I backed up.

"Is that bad?" I said, feeling hotness rush into my cheeks. It sounded serious.

"No. It just means that you will never be able to tune a violin."

"Oh. And I would have to be able to tune a violin to be in the orchestra?"

"Yes. But you don't have to tune a violin to be in the choir. You will fit in nicely there. Just be sure to listen to the people around you and try to blend in."

"Okay," I said, and I picked up my backpack.

"Oh Honey," says my mom, when I explained why I was late getting home from school. "It's not your fault. You got that from your father. He's tone deaf too."

I was shocked.

Had the world's best known singer of, Down by the station early in the morning , and the leader of every, Happy Birthday to you, been singing off key my entire life?

Yes.

One year later my sister Louisa was in fourth grade.

"Good luck," I said when she signed up to be in the Crestwood Elementary School Band. Because she could.

She came home with a French Horn.

Louisa practiced diligently, sitting on her bed, in our shared room down in the basement.

"Do you have to play that thing in here?" Kiki says.

"Yep. Dad says this is where I have to practice."

Obviously, my father was brilliant.

Just because a person is tone deaf, it does not mean that a person cannot tell when music sucks.

"Yes Louisa, I am aware that you can hear me."

As brilliant and tone deaf as my dad was, he loved music.

Good music.

All kinds of music.

He was a huge fan Tchaikovsky's Swan Lake.

He adored the Dorsey brothers, both Tommy and Jimmy.

There could never be too much Duke Ellington, Glen Miller, Theresa Brewer, Mel Torme, SatchMo or B.B. King, as far as he was concerned.

And he could dance up a storm too, just as long as it was to Stardust, and he was hanging onto my mother.

He could also tap his toes, exquisitely.

It was a shame that my parents had to pass up seven dollar tickets to see Frank Sinatra in their early days when they had six little Catholic mouths to feed, but things improved over time.

They managed to squeak in a Tony Bennett concert in a field and they made it to a Woody Herman show.

The six of us all grew up and eventually we left our perfect childhoods.

While lots of other peoples parents were out catching the early bird specials, my empty-nesting parents used their new found freedom to cruise the live music scene.

"How does that voice come out of that cute little thing?" said my dad after hearing Susan Tedeschi wail into a microphone, in Louisville.

They sat in nice seats to see Lyle Lovett and his Big Band at the Barrymore.

They were regular followers of West Side Andy, listening to the great harmonica and piano playing.

They drove up to the Dells and spent an evening with The Charlie Daniels Band and good old Willie Nelson.

They frequented places like the Harmony Bar and The House of Blues, catching venues such as, The Subdudes, Paul Black and the Flip Kings, Marques Bovre and the Evil Twins and Who the Hell is John Eddie? with us kids.

Jackie Greene played at The Majestic Theatre. They were there.

Many a warm summer night they could be found sitting at a long picnic table that was covered in pitchers of good beer and trays of piping pizza, surrounded by their family, all soaking up the talent on the stage, the fine weather and their good fortune to be a part of the entire scene.

My dad was head over heels for Marcia Ball's long legs and er-uh, her bluesy voice.

He really liked the blues.

On his sixty-sixth birthday, in the year 2000, my mom wanted to be sure to get him something that he would love.

After all, he always found really nice gifts for her.

That night the two of them enjoyed a couple of medium rare filets by candle light.

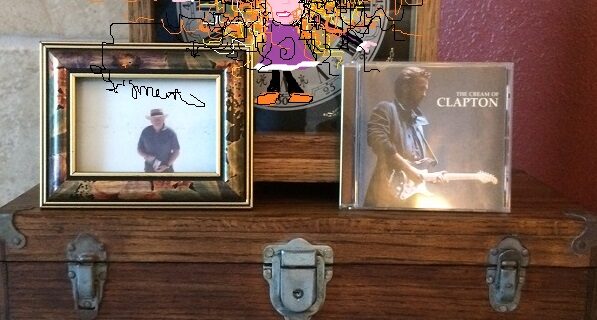

They cleared the plates, poured another glass of Cabernet and my mom handed my dad his present.

"Oh, what could this be?" says my dad, turning the obviously wrapped CD over and over in his hands. "Is it a basketball?"

"Kerm! You always guess it," she says.

She watches him tear a little piece in the corner of the gift wrap and pull it across the CD, revealing a picture of Eric Clapton.

He pauses.

He takes the CD out of the wrapping and drops the crumpled paper on the table.

He holds it up with a puzzled look.

"Don't you like it?" she says, taking a sip of her Cabernet.

And then he says, "Eric Clapton is white?"

And then my mom spit out that expensive wine.

At his family birthday party the next week, we all, as in his kids, their spouses and a heap of grandkids, had a good laugh around the table.

"I just assumed he was black."

"You never saw him on TV?"

"He watches TV with his eyes closed," said my mom.

"Oh."

"But," she says. "I've never seen Eric Clapton. And I knew he was white."

Well, my dad loved that CD, regardless of Eric's color.

I think my dad and Eric Clapton have a lot of similarities.

They both liked pretty women.

Eric has had a few of them over the years.

My dad fell in love and married the first beauty that came along who ordered a hamburger and a chocolate shake, on their first date.

Eric plays the guitar like nobody else.

My dad had a an absolutely gorgeous mandolin that hung on the wall.

Eric signs autographs.

My dad signed off his emails with, Cheers, D.

Eric has had his fill of struggles with the addiction of drugs and alcohol.

My dad liked to sip on a good Scotch now and then. He took an aspirin if he had a headache. And he smoked three cigarettes every Friday, no matter what the hell was going on.

They both got up every morning to put their pants on, one leg at a time.

They both put an X in the box that says, Caucasian.

And they both have music in their souls.

But, Eric is still with us.

My Dad is not.

After several years of missing him I finally understand what it means to say that he is right here, in my heart.

Because that is exactly where I put him.

To this day, I do not eat a piece of cold lunchmeat without hearing his voice, "Millie, put two slices of bread around that. And don't stand there with the refrigerator door wide open."

I do not ladle gravy into the perfectly hollowed out hole in my mashed potatoes without hearing, "Millie, you don't have to make an artwork out of it."

I do not go outside in my socks.

I do not run in the house.

For the most part I have stopped jumping on beds.

When my eyes fill up with water at a parade, I know who's eyes they are.

The smell of cream soda and the sight of an ice cream cone, make me think of just one person.

No bad pun goes unnoticed.

I do not copy and paste in Word, without seeing that glimmer of light in those deep set, thoughtful brown eyes of his.

And I copy and paste, a lot.

I am still waiting to bump into somebody who can tell a joke half as good as my dad.

I NEVER EVER double dip.

Nor does my son, Marques.

I understand that, yes, my reputation really does precede me.

But it's a little late.

I am still working on just sitting down on the couch instead of flopping on it.

And, for the rest of my life, whenever I turn off a light switch in a deserted room, I will smile.

Today my dad would have been 83.

Millie,

You know how I feel about favorites.

Life is not a popularity contest.

I think you should quit antagonizing your sister.

Keep up the good work with your writing. Someday you are going to make it. But I am guessing that you will not be hanging out with me when that happens.

Most importantly, take good care of your mother.

Cheers,

D

"WHO SAID THAT?"